Plate Tectonic

a theory explaining the structure of the earth's crust and many associated phenomena as resulting from the interaction of rigid lithospheric plates which move slowly over the underlying mantle.

Types

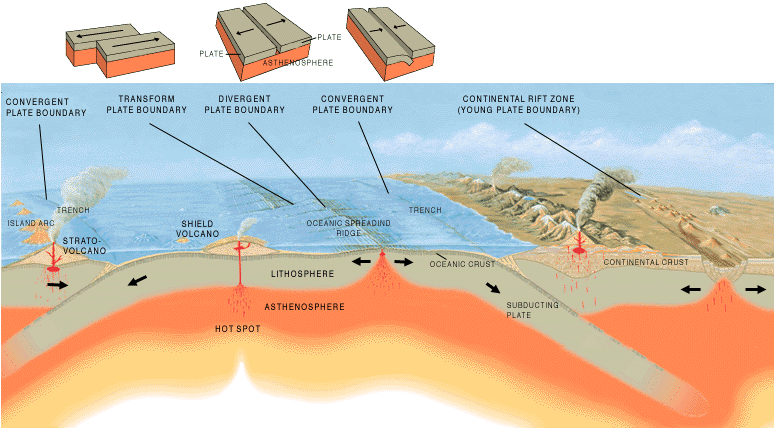

Three types of plate boundaries exist, with a fourth, mixed type, characterized by the way the plates move relative to each other. They are associated with different types of surface phenomena. The different types of plate boundaries are.

Transform boundaries (Conservative) occur where two lithospheric plates slide, or perhaps more accurately, grind past each other along transform faults, where plates are neither created nor destroyed. The relative motion of the two plates is either sinistral (left side toward the observer) or dextral (right side toward the observer). Transform faults occur across a spreading center. Strong earthquakes can occur along a fault. The San Andreas Fault in California is an example of a transform boundary exhibiting dextral motion.

Divergent boundaries (Constructive) occur where two plates slide apart from each other. At zones of ocean-to-ocean rifting, divergent boundaries form by seafloor spreading, allowing for the formation of new ocean basin. As the continent splits, the ridge forms at the spreading center, the ocean basin expands, and finally, the plate area increases causing many small volcanoes and/or shallow earthquakes. At zones of continent-to-continent rifting, divergent boundaries may cause new ocean basin to form as the continent splits, spreads, the central rift collapses, and ocean fills the basin. Active zones of Mid-ocean ridges (e.g., Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise), and continent-to-continent rifting (such as Africa's East African Rift and Valley, Red Sea) are examples of divergent boundaries.

Convergent boundaries (Destructive) (or active margins) occur where two plates slide toward each other to form either a subduction zone (one plate moving underneath the other) or a continental collision. At zones of ocean-to-continent subduction (e.g. the Andes mountain range in South America, and the Cascade Mountains in Western United States), the dense oceanic lithosphere plunges beneath the less dense continent. Earthquakes trace the path of the downward-moving plate as it descends into asthenosphere, a trench forms, and as the subducted plate is heated it releases volatiles, mostly water from hydrous minerals, into the surrounding mantle. The addition of water lowers the melting point of the mantle material above the subducting slab, causing it to melt. The magma that results typically leads to volcanism.[13] At zones of ocean-to-ocean subduction (e.g. Aleutian islands, Mariana Islands, and the Japanese island arc), older, cooler, denser crust slips beneath less dense crust. This causes earthquakes and a deep trench to form in an arc shape. The upper mantle of the subducted plate then heats and magma rises to form curving chains of volcanic islands. Deep marine trenches are typically associated with subduction zones, and the basins that develop along the active boundary are often called "foreland basins". Closure of ocean basins can occur at continent-to-continent boundaries (e.g., Himalayas and Alps): collision between masses of granitic continental lithosphere; neither mass is subducted; plate edges are compressed, folded, uplifted.

Plate boundary zones occur where the effects of the interactions are unclear, and the boundaries, usually occurring along a broad belt, are not well defined and may show various types of movements in different episodes.

a theory explaining the structure of the earth's crust and many associated phenomena as resulting from the interaction of rigid lithospheric plates which move slowly over the underlying mantle.

Types

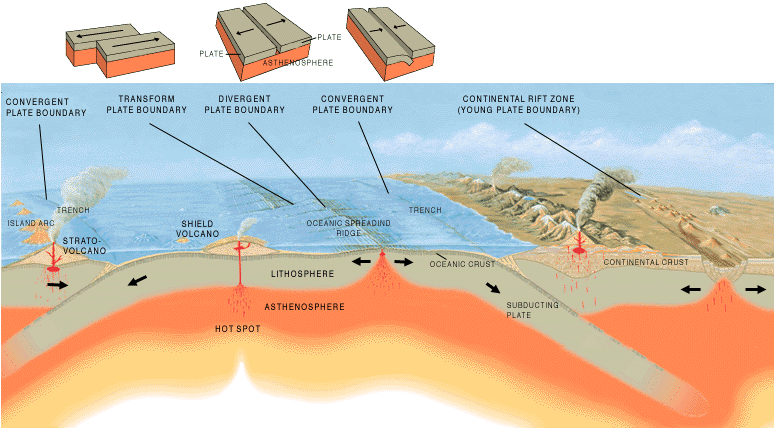

Three types of plate boundaries exist, with a fourth, mixed type, characterized by the way the plates move relative to each other. They are associated with different types of surface phenomena. The different types of plate boundaries are.

Transform boundaries (Conservative) occur where two lithospheric plates slide, or perhaps more accurately, grind past each other along transform faults, where plates are neither created nor destroyed. The relative motion of the two plates is either sinistral (left side toward the observer) or dextral (right side toward the observer). Transform faults occur across a spreading center. Strong earthquakes can occur along a fault. The San Andreas Fault in California is an example of a transform boundary exhibiting dextral motion.

| Transform boundaries |

Divergent boundaries (Constructive) occur where two plates slide apart from each other. At zones of ocean-to-ocean rifting, divergent boundaries form by seafloor spreading, allowing for the formation of new ocean basin. As the continent splits, the ridge forms at the spreading center, the ocean basin expands, and finally, the plate area increases causing many small volcanoes and/or shallow earthquakes. At zones of continent-to-continent rifting, divergent boundaries may cause new ocean basin to form as the continent splits, spreads, the central rift collapses, and ocean fills the basin. Active zones of Mid-ocean ridges (e.g., Mid-Atlantic Ridge and East Pacific Rise), and continent-to-continent rifting (such as Africa's East African Rift and Valley, Red Sea) are examples of divergent boundaries.

| Divergent boundaries |

Convergent boundaries (Destructive) (or active margins) occur where two plates slide toward each other to form either a subduction zone (one plate moving underneath the other) or a continental collision. At zones of ocean-to-continent subduction (e.g. the Andes mountain range in South America, and the Cascade Mountains in Western United States), the dense oceanic lithosphere plunges beneath the less dense continent. Earthquakes trace the path of the downward-moving plate as it descends into asthenosphere, a trench forms, and as the subducted plate is heated it releases volatiles, mostly water from hydrous minerals, into the surrounding mantle. The addition of water lowers the melting point of the mantle material above the subducting slab, causing it to melt. The magma that results typically leads to volcanism.[13] At zones of ocean-to-ocean subduction (e.g. Aleutian islands, Mariana Islands, and the Japanese island arc), older, cooler, denser crust slips beneath less dense crust. This causes earthquakes and a deep trench to form in an arc shape. The upper mantle of the subducted plate then heats and magma rises to form curving chains of volcanic islands. Deep marine trenches are typically associated with subduction zones, and the basins that develop along the active boundary are often called "foreland basins". Closure of ocean basins can occur at continent-to-continent boundaries (e.g., Himalayas and Alps): collision between masses of granitic continental lithosphere; neither mass is subducted; plate edges are compressed, folded, uplifted.

| Convergent boundaries |

Plate boundary zones occur where the effects of the interactions are unclear, and the boundaries, usually occurring along a broad belt, are not well defined and may show various types of movements in different episodes.